These articles are about the Army when I did my National Service. They were written with the aid of a five-year diary and later between working hours during early morning shifts.

A SOLDIER'S TALE (14)

Another evening, spent drinking in the Fleet Club, we were lucky to reach our billets unscathed. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders had stormed into town after weeks under canvas in the New Territories. On arrival at the club, they found there were sailors present. I did not know if it a case of "Hullo, sailor", or "Watcher wearing under that kilt then?" that sparked the row. But within minutes we were surrounded by brawling, panting, sweaty men punching and kicking hell out of one another. Stopping only to swallow our beer, we gingerly picked our way through flying bodies, dodging a chair there and a bottle here, towards the exit. Discreetly - almost demurely - we minced along under the suspicious gaze of a squad of military police waiting with the patience of tigers for the fighters to exhaust themselves. Then packed them away into the Bedfords lined up on the streets outside to cool their ardour for the night.

In the morning, a cheer from the half-shaven occupants of the next door billet as they greeted an errant storeman, who, in spite of a hangover, and the loss of his beret and belt, was jubilant over the doubtful fame of having participated in the glorious battle. He had heard it was the biggest and best fight that ever occurred at the Fleet Club. This appeared to be confirmed later when daily orders included a terse comment that the naval "brass" warned that if the army could not behave better in future soldiers would be banned from the Fleet Club. We tutted all the way to the abnormally quiet, sparsely-furnished bar the next evening. "Bet you ten thousand pounds you daren't say "Hullo sailor" urged Johnny.

A somewhat less alcoholic occasion was Chinese New Year, when the colony became a battlefield of fireworks for three days, and firecracker explosions rent the air day and night. The custom was to load one's pockets with bangers and hurl them about the streets with great abandon. All the busier inhabitants were quite unconcerned.

I suppose it was inevitable that eventually the firework throwing could cause a racial confrontation. Four or five of us were making our way slowly to the Lee cinema, good-humouredly lobbing bangers into doorways. But as we the mounted the steps of the cinema, the explosions became more frequent, the throwing more accurate, and gone was the casual atmosphere we had experienced during the walk from the barracks. With crackers exploding literally about our ears and around our feet, we turned to face a semi-circle of young and impassive Chinese faces strung out across the road. They knew us for soldiers and it seemed were out to get us. The atmosphere was electric. We, too, were lighting and throwing crackers as fast and hard as we could. The light-hearted evening was being replaced by something more sinister.

Then, my right hand was knocked sideways and I felt a stab of pain, followed by numbness. A cracker with a short touch-paper had exploded in my hand. I was a casualty, and any enjoyment I may have had out of Chinese New Year was over. "Stretcher-bearers" I gasped to Mike, holding my hand. "White flag" came rejoinder, and as one man, we turned and fled ignominiously into the foyer of the cinema. The manager frowned as crackers hissed through the open doors and exploded on his clean floor. Suddenly it was quiet, and the battle of the Lee was over. Much chastened and with new insights into crowd behaviour we went in to the film during which I nursed my throbbing hand.

All this was highly enjoyable, irresponsible fun - most of the time anyway. But it was not getting the best out of the 12,000-mile trip across the world at the Government's expense. It was here that family contacts in the colony lifted me out of the barracks and beer routine. But family contacts however, are all very well if there is no meeting point - some sort of spiritual "nicking" of mutual interest - can fail. One of these was perhaps typical. He was an elderly business man, a widower, whom lived in a charming house on the Peak. I was on my best behaviour. We dined - yes, dined - at each end of a lengthy table waited on by two amahs. It was like something out of a Victorian novel. When the strengthening wind rattled a window and my host said we ought to shut it, I jumped up to help. One of the amahs quelled me with a scornful look as she hastened to her master's suggestion. Truly, I was out of my depth.

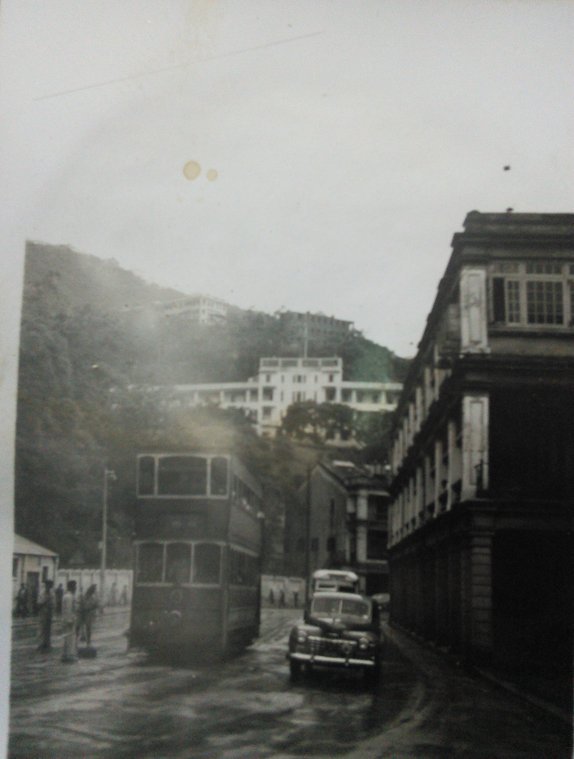

As the delightful meal of Chinese delicacies wound its way to its conclusion, the evening became full of eerie foreboding. The wind was blowing itself into a typhoon. "You ought not to be late getting back" my host said. As it was, the Peak Tramway had stopped running. So an intrepid taxi driver drove me back through the debris of broken branches, flying rubbish and the shrieking wind. Then, as we rounded a hairpin bend there was a flash from the harbour, followed by a thud of an explosion. "Mao Tse Tung must be coming", flashed my driver. I agreed, not very happily. I was glad to reach the comparative snugness of the billet where storm shutters were tightly closed against the battering, blinding winds and now rain. My arrival was greeted variously by: "Cor, look what the wind's blown in?", and "Good evening, Lady Macbeth".

All night we lay awake listening to the tempest and feeling the building shudder, sheltered as it was. Occasionally items would thud against the shutters, and once a tin can bounced down the verandah as if chuckling at the triviality of Man and his works when faced with the wrath of Nature. We expected daylight to reveal collapsed buildings at the very least. But apart from scattered tiles and debris there was no damage - not in the barracks anyway. Later at work we heard of the troops in the New Territories being washed out, and our view of the harbour showed us angry waves lashing the ships at anchor, several of whom had dragged anchor and run aground. And in the middle of all lay the wreck which had blown up. The blast nothing to do with the typhoon, but we were not vouchsafed the reason for it. Over our tea we muttered darkly about ammunition...

A more lasting relationship was formed with a Mr Everest, the manager of a Chinese style amusement park on the mainland. I believe he had been among Hong Kong's liberating troops at the end of the war and had settled in the colony. His "park" consisted largely of mahjjong "huts" from which emerged cries of triumph or sorrow as the locals indulged in their favourite gambling game.

Of more immediate interest to me, however, was the hospitality of my burly, good-natured host. Frequently I had to have a late night rickshaw from the Star Ferry to get back to the island and the barracks before my pass expired. Through Mr Everest I met his son Barney, a police officer, and his charming wife Peggy. I remember eating a memorable meal of vindaloo curry with chapattis and beer in their Kowloon flat and later spent a day when they were posted to the nearby Cheung Chau island police station. It was an island idyll, with no cars, and chosen by many orientalised Westerns for their retirement.

To be continued...